The GoodMills Group is the leading milling company in Europe, managing 7 country organizations with 24 flour mills. As Europe’s largest flour producer, processing 2.8 million tons of grain annually, we are relentlessly focused on providing a valuable source of nutrition for millions of consumers every day.

We want to bring out the best of grains and pulses to make it the best ingredient for delicious food in all variations.

LATEST

NEWS

We are excited to inform you about latest events and stories that matter.

Read insightful industry information, statements and articles about milling trends and gain insight into our company and brands.

January is VEGANUARY!

Jan 2024

GoodMills is not only Europe’s largest milling company and manufacturer of popular flour brands for the home, but also a key player in the market for plant-based products. A recent EU-funded survey, conducted by ProVeg International in collaboration with University of Copenhagen (Københavns Universitet) and Universiteit Gent, unveiled that the meat consumption in Europe is ... Home

read moreGoodMills is "Proud Partner" of CONCORDIA

Oct 2023

As a long-time partner and founding member of CONCORDIA’s “Impact Angels”, GoodMills has prolongued the cooperation and became “Proud Partner” of the NGO. The partnership between CONCORDIA and GoodMills has recently been elevated to a higher level: as a “Proud Partner”, GoodMills joins a group of corporate partners who have been supporting and accompanying CONCORDIA ... Home

read moreGoodMills at the 16th International Danube Exchange

Sep 2023

On 1 September, the annual Danube Exchange took place in Vienna again. This industry meeting of grain and feed trade, processing and logistics the event attracted many visitors from Central, Southern and Eastern Europe to discuss qualities and prices with industry representatives directly after harvest. As the leading flour milling company in Europe, the Danube Exchange is ... Home

read more

OUR 3

STRATEGIC

PILLARS

We focus on 3 major areas, commodity being our DNA, innovation & brands our accelerators.

INDUSTRIAL MILLING

Providing reliable supplies of high-quality flour to large industrial clients, bakeries and other business partners.

learn more

INNOVATION

Driving the industry by developing outstanding solutions for raw materials that add value for our partners.

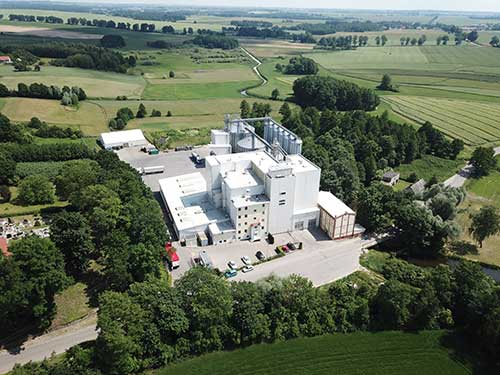

learn moreOUR LOCATIONS

OUR PEOPLE

Achieving better, together

We owe the fact that we are Europe’s largest milling company to our great team!

Our success is directly linked to the outstanding contributions of our employees in all countries and our dedicated management teams. We know not only what our customers and consumers need, but also what our employees need to grow together with us.

Together, we are GoodMills!

MEET OUR

MANAGEMENT TEAM

The GoodMills Group Executive Board is the body that manages our company. The members have each individual areas of responsibility and together they form a strong leadership team for our company.

learn more about them